You might reconsider eating farmed salmon after reading this article—apologies for any changes to your menu this week.

For days, you’ve been dreaming of this sashimi platter, carefully crafted by a sushi master with a blade as sharp as a samurai sword. The evening promises to be perfect in this trendy Japanese restaurant in London as your salmon arrives on a beautifully decorated plate, transporting you directly to one of Tokyo’s fish markets.

But as you unsheathe your chopsticks, you mark a pause. Lately you have become more interested in questions of origin and sustainability – especially regarding your food, and you wonder: where does this salmon come from, how was it caught, and what is its story? Then you tell yourself you’ll think about it later. For now, it’s time for more miso sauce.

Like hundreds of thousands of Londoners, you likely encounter salmon almost daily. It has become a staple in our lives, found on our tables, in markets, supermarkets, restaurants of all types, fast-food chains, bakeries, and, of course, poke bowls, where it’s all the rage. Salmon mania is featured on TV, in newspapers, and across social media.

Why has salmon become so trendy, especially in big cities and is it the start of the salmon era ?

When we think about salmon, we might imagine pristine waters in Alaska, a BBC documentary with bears feasting before winter, or just Christmas, protein, and omega-3 fatty acids. There is something to spark everyone’s imagination. Salmon is pretty easy to cook, has become relatively affordable, is a favourite delicacy and goes well with broccoli—creating that perfect “Instagrammable dish” you see everywhere, far from the traditional fish and chips.

It’s often hailed as a “healthy” choice by gym bloggers, packed with those good fats we hear so much about.

As climate change continues to be one of people’s main concerns, salmon looks like the perfect alternative to meat, especially beef, and is riding high on that wave.

But what are we really talking about here, and does salmon really walk the talk as a miracle product for your health and the environment?

Wild vs. farmed: What’s the difference ?

There are seven species of salmon, but the one most commonly found in UK supermarkets and restaurants is Atlantic salmon. While wild Atlantic salmon feed on various organisms in oceans, lakes, and rivers, farmed Atlantic salmon are raised from eggs in open-net pens for around 18 months in the cold waters of Scotland, Norway, or Chile, the main salmon farming producers. These eggs become fish, which will be kept alongside tens of thousands of other salmon while being fed with processed food (we’ll come back to that later). The wild Atlantic salmon population is now so low that you are most likely to find farmed Atlantic salmon in supermarkets.

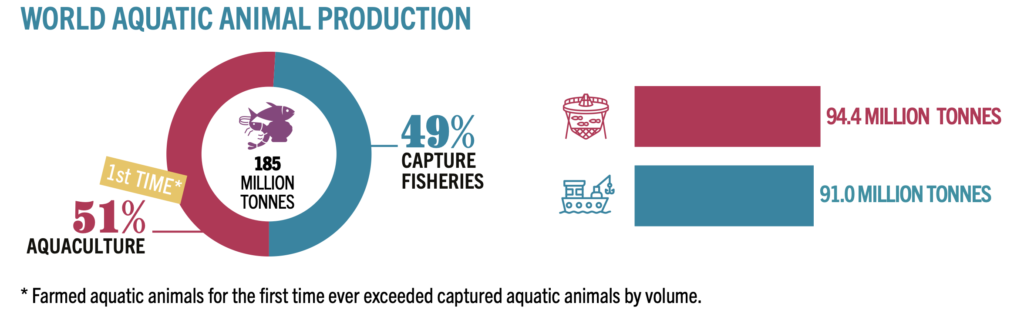

In 2022, for the first time, the production of farmed fish surpassed wild-caught fish, reaching 94.4 million tonnes and representing 51% of the world’s total. Source: The State of the World Fisheries and Aquaculture (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2024)

But at what cost to the environment and coastal communities?

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that aquatic animal production is expected to increase by 10% by 2032, with aquaculture (i.e., fish farming) leading the way.

The FAO has set out a roadmap to ensure this expansion is done sustainably, but it recognises that progress in reaching the Sustainable Development Goal targets has been slow, which is not particularly reassuring and is causing concern among many NGOs.

In the wild, salmon travel over 6,000 miles before spawning, but farmed salmon are confined to cramped conditions, leading to stress and disease.

This situation is similar to the overcrowded conditions of battery-farmed chickens. These farming practices pollute ecosystems with nitrates, faeces, antibiotics, and pesticides, and they pose risks to wild species through escape and interbreeding.

Farmed salmon are often infected with sea lice, a harmful parasite that can spread to wild salmon and other species. Bon appétit!

Whether we like it or not, eating farmed salmon in London has global repercussions, affecting regions such as West Africa and South America. But how? This is brilliantly illustrated in the documentary Until the End of the World by filmmaker Francesco De Augustinis, as well as by non-profit organisations like the Global Salmon Farming Resistance and WildFish.

From the butterfly effect to the salmon effect

Producing 1 kg of farmed Scottish salmon (a carnivorous fish) requires much more than 1 kg of wild fish. To meet this demand, millions of tonnes of small fish like sardines, which are not only perfectly edible but often more nutritious than salmon itself, are taken from the Global South and used as feed for farmed salmon. The salmon is then sold in North America, Europe, and Asia.

In summary, not only do communities in Africa not eat salmon or benefit from this business, which is mostly controlled by companies from the Global North, but they also pay the price by losing their livelihoods and having no fish to eat because these fish are used to feed salmon.

This practice, akin to robbing Peter to pay Paul, contributes to food insecurity in the communities where these small fish are harvested, directly opposing what the FAO advocates for. “Why would you eat salmon when you can eat sardines?” should be a reasonable question to ask.

Are there no labels and regulations helping us navigate?

Despite its popularity, salmon farming in Scotland faces significant challenges due to weak regulation and oversight. Currently, there is no UK legislation specifically protecting farmed salmon welfare at slaughter or regulating its environmental impact. NGOs like Feedback and the Animal Welfare Committee have been urging the government to address these issues with effective regulations.

Despite the absence of strong government regulation, third-party certifications like the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC), the Soil Association’s Organic standard, and RSPCA Assured aim to raise standards, but according to WildFish, these schemes often contribute to greenwashing, misleading consumers into paying a premium for what they believe are sustainable products, when in reality the claims do not hold up to scrutiny.

On the other hand, Tavish Scott, CEO of Salmon Scotland, argues that Scottish salmon is the UK’s most popular fish and its No. 1 food export, supporting many jobs. He believes the industry should not be threatened by what he calls a small group of “urban-based activist chefs.” This highlights the tension between economic interests and environmental concerns, a conversation that we, as consumers, can influence since farmed salmon is the most consumed fish in the UK, with 70% of the salmon consumed here being farmed. It’s also the largest fish farming sector in the UK, producing around 205,000 tonnes in 2021, and is both Scotland’s and the UK’s top food export.

What does this mean for Londoners, and are there alternatives?

As Londoners, our choices can have a big impact on the environment and the food industry. We have the power to drive change by reducing demand—why not eat less farmed salmon or avoid it altogether?——and by advocating for stronger regulations that clearly define sustainable fish farming practices.

You can also support restaurants involved in the “Off The Table” campaign, which refuse to serve open-net farmed salmon. Some UK chefs and restaurants, like Chantelle Nicholson, chef and owner of London’s Apricity, have joined this campaign because of concerns about environmental damage. Many of London’s main museums have also signed up. By choosing these places to eat, you can make sure your dining choices reflect your values. Even Wimbledon chose not to serve salmon at the 2024 tournament. You might also want to support the Fish Farms Out campaign. It brings together 160 organisations and is calling for fish farming to be excluded from sustainable aquaculture policies.

Exploring alternatives is another way to make a difference. Instead of farmed salmon, why not try more sustainable fish like mackerel, anchovies, or sardines? They’re full of nutrients and have a lower environmental impact. Other good options are oysters, mussels, and algae. Algae, which is high in fibre and fatty acids, is a great addition to a healthy diet. Seaweed, a type of algae commonly used in Asian dishes, is a fantastic choice. One of our favourites is Japanese seaweed salad, or wakame, which is easy to make at home. For those interested in plant-based options, there are plenty of shops across London, and plant-based products are often available at regular supermarket stalls.

The Green Londoner’s takeaways:

-

- Get informed: Despite green labels, farmed salmon is not sustainable. It significantly impacts the environment and local communities.

-

- Ask when in doubt: Just say no when you encounter farmed salmon.

-

- Share information with family and friends: Change always starts within close circles, as the level of awareness on this topic remains quite low.

-

- Adjust your diet: Opt for wild salmon or alternatives like mackerel, anchovies, or sardines—or even better, algae and plant-based substitutes if you’re leaning towards a plant-based diet and want to try new things.

-

- Support organisations: Get involved with The Global Salmon Farming Resistance, WildFish, the Off The Table campaign, the Rauch Foundation, and many more.

We’ve joined the Global Salmon Farming Resistance network to tackle the problems with farmed salmon, both here in London and worldwide. And yes, you can take action right from London too.