Wood burning is a cozy winter tradition for many, but it’s also a significant contributor to air pollution in cities like London. To shed light on this issue, we spoke with Peter Knapp (see photo), an Air Quality Scientist, to explore the health implications of wood burning, its role in urban air pollution, and how Londoners can take meaningful action.

The Green Londoner – In recent weeks, particularly during weekends, London’s air quality has experienced a noticeable dip. Could wood burning be a contributing factor, and why does it resurface as a recurring topic each winter?

Peter Knapp- The smell of the air around London over the last weekends is enough to tell you that wood burning is a significant part of the air pollution. Scientifically, the composition of ambient PM2.5 in London highlights this, as seen here. During air pollution episodes, particularly at week-ends, the green band shows the organic mass, which is predominantly wood burning.

It’s worth noting that DEFRA (Department for Environment) provides weak PM2.5 targets, considering anything under 35 µg/m³ as low, compared to the WHO guideline of 5 µg/m³. Looking back at just two days ago (Saturday, 18th January), the PM2.5 level in London reached 32 µg/m³—more than six times the limit recommended by the World Health Organization!

Wood burning is an emotive topic, even among environmentalists, because it’s tied to comfort and tradition. Global Action Plan has produced a helpful report on addressing behavioral change around wood burning: Toolkit for BehaviouralApproaches to Wood Burning.

Burning wood in a stove while watching a movie, comfortably seated on a sofa, seems like the perfect way to spend a cold January day. After all, it’s legal. But is it really a good idea for those burning the wood? What about the neighbors and the city as a whole?

I understand the draw to fire—it’s mesmerising. G.F. Bradby’s poem Fireside captures this perfectly: “In the ember’s drowsy glow; Fiery figures come and go; Quiver into crimson light; Now a goblin, now a knight’.” However, just as smoking in pubs is no longer acceptable because of its impact on others, we need to balance personal freedom with the effects on public health (see my TV interview on GB News with Laurence Fox here).

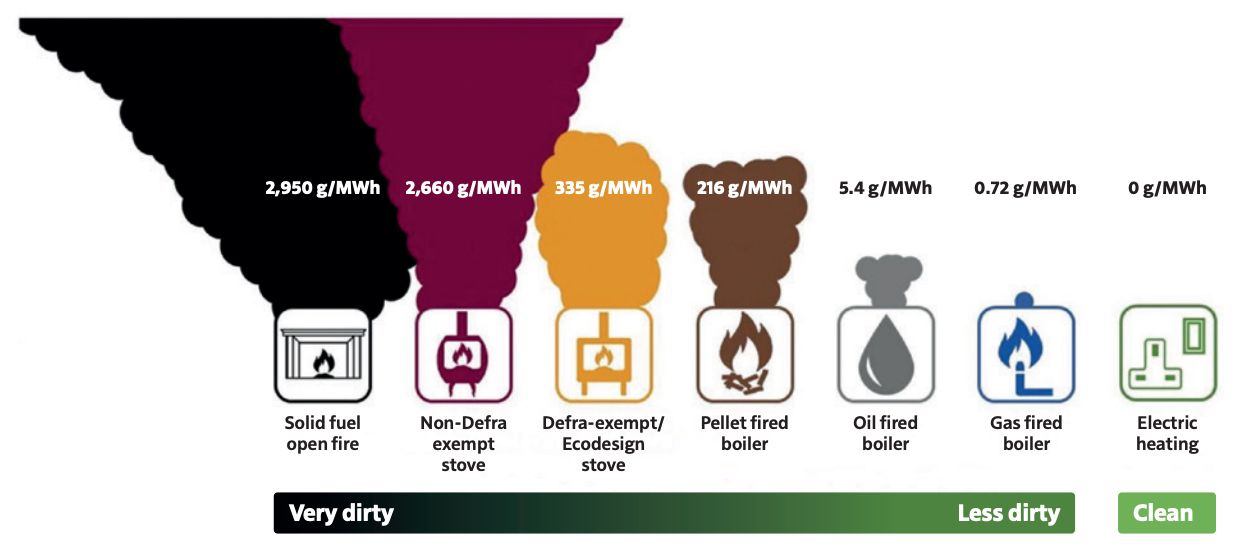

Wood burning rules vary. In Smoke Control Areas, only DEFRA-approved stoves and fuels are legal. However, these stoves are far from problem-free:

- Particle numbers vs. mass: DEFRA-approved stoves produce more ultrafine particles than non-approved stoves. Measuring pollution by mass overlooks the health risks posed by particle numbers.

- Toxicity over time: Particles change as they move, potentially becoming more toxic. For example, wildfire smoke becomes four times more harmful after a day, and we don’t yet know if the same applies to wood smoke.

- Geographical impact: Valleys trap smoke, exposing residents to higher concentrations.

Considering the health consequences of wood burning, there are two main groups to consider: the people burning the wood; and the people living nearby. People who burn wood will be exposed to elevated levels of air pollution that children in the household may also be exposed to.

Burning wood releases PM2.5 and PM10 particles. Could you explain what these particles are and why they’re a concern, especially for children?

PM2.5 refers to particles smaller than 2.5 microns—about 1/20th the width of a human hair. These particles can penetrate deep into the lungs, causing inflammation and chronic illnesses. PM2.5 is primarily produced by burning materials or through chemical reactions in sunlight (see more details here).

The Chief Medical Officer’s 2022 report highlighted that domestic wood burning is a major source of fine particulate matter emissions in the UK, contributing to between 26,000 and 38,000 deaths annually in England. Children are particularly vulnerable, with studies showing that air pollution stunts lung development and increases the risk of asthma, allergies, and heart disease. In London, children in polluted areas experience lung volume reductions equivalent to losing the size of two large eggs.

Although it’s important to understand that the air pollution from wood burning is different to the gases from traffic exhausts, both cause inflammation and both contribute to similar health effects.

Open fires and stoves are the two main ways of burning wood in London. Which is more popular, and which is less harmful?

Open fires are often blamed for wood smoke, but stoves now account for 75% of air pollution from wood burning, compared to just 3% in 1970. While stoves burn more efficiently, they produce more ultrafine particles, which are most dangerous. I spoke about the difference between open fires and wood burning stoves on BBC 5Live with Nicky Campbell.

Open fires in pubs or homes within Smoke Control Areas are illegal. If you spot one, report it to the landlord or council. The Chief Medical Officer’s report identified open fires as the dirtiest form of indoor heating, with electric heating being the cleanest alternative.

With the well-documented harmful effects of wood burning, why is it still permitted in the UK?

The UK has one of the worst asthma death rates in Western Europe, and 40% of children here have allergies, likely linked to air pollution. Yet, the government avoids banning wood burning, citing reliance on solid fuels for heating in some rural areas.

The previous Tory Governments ignored the fact that only 6% of households burn wood due to necessity. The government should have supported these households with insulation and heat pumps instead of allowing affluent urban areas to pollute their neighborhoods.

In regions like the South East, where wood burning is most common, most homes have access to alternative heating. This suggests that political will, rather than necessity, drives inaction on banning wood burning.

Should London follow other cities, like those in the Netherlands or Italy, and ban wood burning outright?

Yes. Cities like Utrecht are phasing out wood burning entirely by 2030, recognising its harmful impact. The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has banned wood burners in new developments, but this alone won’t solve the problem.

Wood burning in urban areas is often a choice, not a necessity, for many households, costing around £1,000 per heating season for kiln-dried wood. It’s time for London to adopt a total ban on wood burning, just as progressive cities have done.

For those who still burn wood, what practical alternatives or practices would you recommend to reduce their environmental and health impacts? What advice would you give Londoners who want to act responsibly?

For the 6% of households that rely on wood burning, I recommend improving insulation and switching to heat pumps. Government grants are available for both:

For those burning wood out of habit, consider the impact on your neighbors. Reducing usage or switching to cleaner alternatives is a simple way to act responsibly.

From a practical perspective, awareness is crucial. Are there any apps you’d recommend for tracking air pollution levels in London?

For London, I use:

For the UK and Europe, I use:

Finally, we’ve heard a lot about indoor air filters. Do they actually help when outdoor pollution levels are high? If so, do you have any recommendations?

Yes, air filters help clean the indoor air. For my home, I use:

- SmartAir cleaning units SA600 for the bedroom (quiet and low airflow) and the Blast Mini for the kitchen (louder but cleans much faster during cooking)

- QP Pro for monitoring the air quality

- Smart plugs to turn on the air cleaners if I see the air is polluted when I’m on my way home and I can turn them on to have clean air when I get back.